[ad_1]

As part of an effort to keep illegal drugs and other contraband out of state prisons, New York is taking away one of the few pleasures of life behind bars: It will no longer let people send inmates care packages from home.

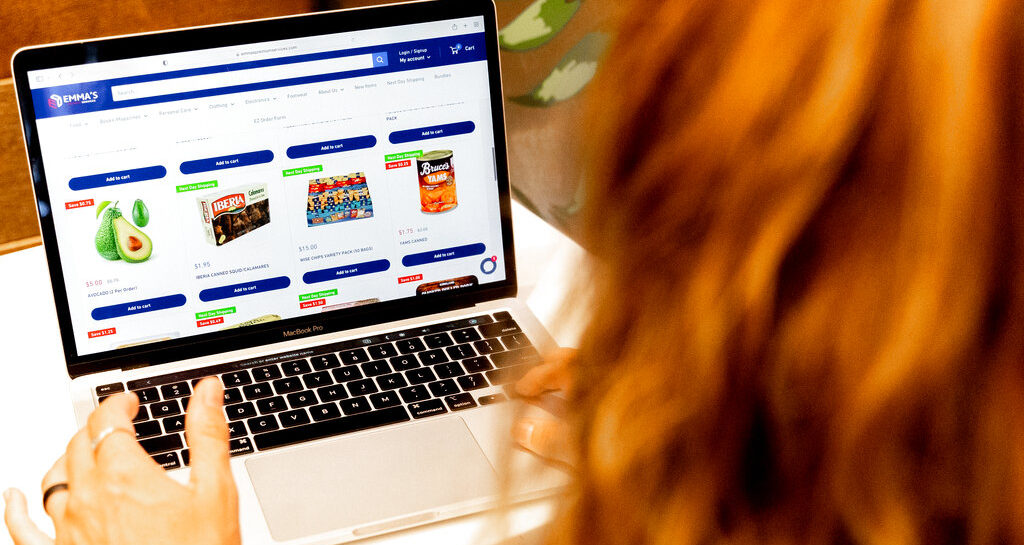

Under the new policy, which the state began phasing in last month, friends and family aren’t allowed to deliver packages in person during prison visits. They also won’t be allowed to mail boxes of goodies unless those come directly from third-party vendors.

While the rule won’t stop prisoners from getting items that can be ordered online, like a Snickers bar or a bag of Doritos, they will lose access to foods like home-cooked meals or grandma’s cookies.

That’s a letdown for people like Caroline Hansen, who for 10 years hand-delivered packages filled with fresh vegetables, fruits, and meats to her husband, who is serving a life sentence.

“When I first started bringing him packages, he said he loved avocados. He hadn’t had them in about 20 years,” said Hansen, a single mother of two who works as a waitress in Long Island.

“What breaks my heart is, I take for granted having a banana with my yogurt. Imagine never being able to eat a banana?” she added, saying her husband’s prison cafeteria serves bananas once a month, at most.

New York had been one of the few states in the nation that still allowed families to send packages to inmates from home. The rule is already in effect in a majority of state prisons.

Starting this month, the state prison system is also testing a program where inmates will be blocked from getting most letters sent on paper. Instead, incoming letters will be scanned by computer, and prisoners will get copies.

The change is being made to try and head off a trend of people soaking letters in drugs to smuggle them past authorities. Multiple states including Ohio, Wisconsin, Michigan, Nebraska and Pennsylvania, already photocopy incoming mail to prevent drugs from being delivered to inmates. The federal Bureau of Prisons began a similar practice in 2019.

New York’s Department of Corrections and Community Supervision said in a statement that the two new policies are necessary to stop contraband.

Contraband has been smuggled into prisons in a number of ways: books laced with heroin, weapons and unauthorized electronics like phones hidden in packages, and letter mail soaked in drugs like methamphetamine or a synthetic cannabinoid, also known as K2.

When packages are received by a prison, officers remove the items from the box to inspect the items visually or through an X-ray machine. If there is reason for suspicion, officers are allowed to open sealed packages for further inspection.

Those checks, though, aren’t perfect, and authorities believe items slip through.

Critics of the package ban questioned its effectiveness, noting that prohibited items are sometimes brought in by corrupt prison staff.

California stopped allowing people to send packages directly to inmates in 2003. Instead, inmates and families can order items through an approved vendor list provided by the state. In Florida, families also aren’t allowed to send packages from home.

Prisoner advocates and families of inmates say the package policy is too restrictive — and an added financial burden.

Wanda Bertram, a communications strategist at the Prison Policy Initiative, called prison food a “nutritional nightmare,” and said some incarcerated people rely on care packages to keep a healthy diet.

Relatives of inmates often rely on private vendors like Walkenhorst and Jack L. Marcus Company, which specialize in sending allowed goods to prisoners, but items bought from third-party vendors can be more expensive.

Before his release from Sing Sing Correctional Facility in New York, former prisoner Wilfredo Laracuente said he was able to order a 35-pound (16-kilogram) package for himself containing packaged cakes, cookies, chips, soaps, shampoo, and some toiletries.

It cost $230 — the kind of money most prisoners don’t have.

“This is going to be the beginning of the end, where they stop everything under the guise of security and contraband,” said Laracuente, who served two decades in prison for murder and now facilitates workshops that help recently released inmates reintegrate into society. “What they’re doing is removing the human component that’s very vital and necessary for the reentry process.”

Even before the ban, families often complained that sending packages was unreliable.

Angelica Watson, whose husband and brother are both incarcerated, said she tried to send packages to them monthly, but food items didn’t always make it through before they spoiled.

“Most of it was nonperishable items,” said Watson, who lives in Buffalo. “I tried to do fresh, but it wasn’t a good idea because they’d hold it in their storage rooms and it would go bad.”

Hansen, whose husband is serving time for killing a cab driver, said having to order goods through vendors that charge “ridiculous prices,” was no solution to the contraband problem.

“My husband basically thinks this is one more way to deprive him of his basic necessities,” Hansen said.

More than 60 families of inmates sent grievance letters to New York Assemblymember David Weprin, the Democratic chair of the Assembly’s Committee on Correction. Weprin criticized the new policy.

The package restriction was first introduced in 2018 through a pilot program at three state prisons, where families could only send packages through a list of six preapproved online vendors. It was quickly rescinded by then-New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo, a Democrat, because of public backlash and criticism.

[ad_2]

Image and article originally from libn.com. Read the original article here.