[ad_1]

By Lawrence G. McMillan

This article was originally published in The Option Strategist Newsletter Volume 4, No. 20 on October 26, 1995.

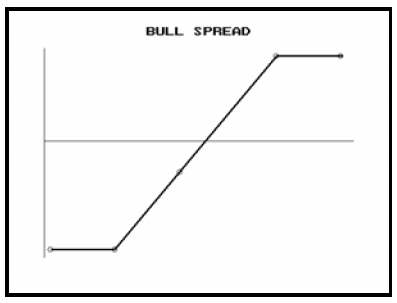

Any spread that creates a debit in one’s account, when it is established, is technically a debit spread. However, when the term “debit spread” is used, it generally connotes either a bull spread with calls or a bear spread with puts. These are types of vertical spreads, since all the options have the same expiration date but have different striking prices (credit spreads are vertical spreads also).

An example of a debit spread using calls would be:

Buy 10 IBM Jan 100 calls @ 5 Sell 10 IBM Jan 110 calls @ 2

Since the call that is being purchased is more expensive than the one that is being sold, a debit is incurred when this spread is established. In this example, the debit would be $3000 plus commissions.

The profit graph above shows the general shape of the profitability of this spread. The maximum risk is the initial debit ($3000 plus commissions). The maximum profit would be realized if IBM were above 110 at expiration. In that case the spread would widen to its maximum extent — and would be equal to the difference in the striking prices, 10 points. This means that the 10-lot example spread could be worth as much as $10,000 less commissions at expiration. This type of ratio between risk and reward makes this an attractive strategy to some.

However, the strategy has some drawbacks as well. First, one can lose 100% of his investment in a short period of time, just as he can with a call purchase. Second, the profit potential is limited. If IBM were to rise to 120 or 130 by January expiration, then larger profits would have been realized by merely owning calls and not using a spread.

What often motivates one to use the spread strategy is that calls are expensive. Thus, one may want to reduce his overall cost by selling an expensive out-of-the-money call against the at-the-money call that is being purchased. Moreover, the probability of making a profit is often better with the bull spread than it is with a straight call purchase. These points can be illustrated best with OEX put options. They are expensive (on a relative basis) and the out-of-themoney puts are even more expensive than the at-the-money puts. Moreover, owning the OEX put debit spread may provide better profit opportunities than merely owning OEX puts. At recent prices, the following spread could be established:

Buy 1 OEX Nov 550 put @ 4 Sell 1 OEX Nov 540 put @ 2½

We will ignore commissions for the purposes of this example. The implied volatility of the Nov 550 put that is being bought is 14%, while the implied volatility of the Nov 540 put that is being sold is 16%. Thus, this particular spread has a theoretical advantage as well, in that the option being bought is relatively “cheap” when compare with the option being sold. All debit spreads don’t have this feature, but when they do, it is a nice advantage.

Note that the bear spreader only pays 1½ points for his spread while the put buyer would have to pay 4 points for the Nov 550 put. Now, let’s look at some of the probabilities of making money at expiration when one compares ownership of the bear debit spread with outright ownership of just the Nov 550 put. First, the debit spreader would double his money is OEX were at 547 at expiration (the long puts would be sold for 3 and the short puts would expire worthless). For the outright put buyer to double his money, OEX would have to be at 542 at expiration.

An even more dramatic difference is evident when “maximum” profits are compared. The debit spreader can make a maximum profit of 567% if the spread widens to 10 (he has a profit of 8½ points on a 1½ point investment). This, of course, would transpire if OEX fell to 540. For the outright put buyer to do as well, OEX would have to fall to almost 523 (at that point the 4-point investment in the Nov 550 put would have grown 567%). Thus, even though the outright put purchase theoretically has a better maximum profit potential, it would take a massive drop in OEX for the outright put purchase to outperform the debit spread.

When viewed in this manner, debit spreads often offer better returns than outright purchases do. The major drawback of the spread, though, is that it won’t normally widen to its maximum potential until very near expiration, while an outright purchase will show profits right away. So, if you are a short-term trader, stick with outright purchases, but if you are more intermediateterm oriented, consider a debit spread instead for it may offer better returns.

This article was originally published in The Option Strategist Newsletter Volume 4, No. 20 on October 26, 1995.

[ad_2]

Image and article originally from www.optionstrategist.com. Read the original article here.